It may even be you, a single developer, who first wishes to work on the header, then perform a commit, work on the footer - perform a commit, again want to work on the header, and so on. Let us take that we are building a react app and one developer is working on the header component and another developer is working on the footer component. There is a saying among developers that start the day by pull, take a break on commit and end the day by push It is a general practice to commit your changes very ofter regularly, so that the changes are not missed. Not removing branches that are stale or have already been merged can cause confusion and make it more difficult than necessary to differentiate new ones.In this post, we will go over why branching is required, the difference between development, staging and production environments, why a strategy is required for branching, and look at a good Git branching strategy. There’s no reason to leave them about – all the work is in master. Keep branches tightly scoped to the one issue they’re meant to close. This results in scope creep and huge, confusing PRs that take a lot of time and mental effort to review. Letting the issue branch live just a little longer.To avoid confusing conflicts and dependencies, always branch off the most up-to-date master. This is a result of poor organization and prioritization. Creating feature branches off of other feature/issue branches.Some common pitfalls I’ve seen that can undermine this flow are: Once everything checks out, the PR is merged, the issue is closed, and the branch is deleted. Depending on the project, you may deploy a preview version as well.

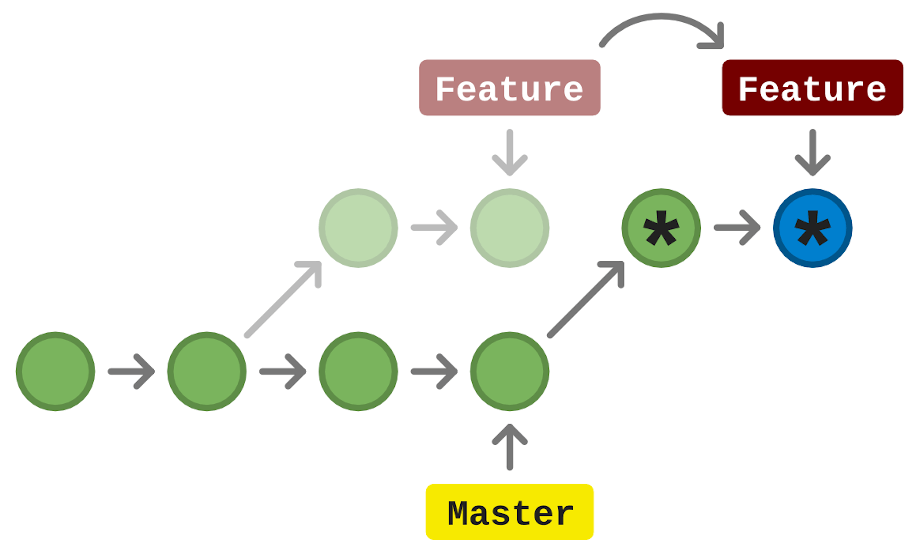

Teammates review the work (using inline comments and suggestions if you’re on GitHub). When the issue work is ready to PR, open the request against master. Since I’m all about reducing cognitive load in developers’ processes in general, I recommend using a merge strategy. Interactive rebasing can easily introduce confusing errors, and rewriting history can be confusing to begin with. This happens to be my personal preference as well, however, I’ve found that people generally seem to have a harder time wrapping their heads around how rebasing works than they do with merging. You may prefer to use rebasing instead of merging in master. # Return to your issue branch and merge in master git checkout 28/add-settings-page # Get the latest work on master git checkout master # Commit to your issue branch git commit. For an issue named (#28) Add user settings page, check out a new branch from master: Generally, strive to iterate in as little time as possible. For open source projects like the OWASP WSTG that depends on volunteers working around busy schedules, branches may live for a few weeks to a few months, depending on the contributor. The definition of “short” varies depending on the team or project’s development velocity: for a small team producing a commercial app (like a startup), the time from issue branch creation to PR probably won’t exceed a week. Author's illustration of issue branches and releases from master.Ī short-lived branch-per-issue helps ensure that its resulting pull request doesn’t get too large, making it unwieldy and hard to review carefully. It could be a new piece of functionality, a button component update, or a bug fix. To take a quick aside, an issue is a well-defined piece of work that can be merged to the main branch and deployed without breaking anything. You’re already doing a great job of tracking future features and current bugs as issues (right?). If you develop on GitHub, the latest tag of this branch gets deployed when you create a release – which is hopefully very often, and very automated. To support continuous delivery, no human should have direct push permissions on your master branch. Having implemented features I like from all of these with different teams over the years, I’ll describe the resulting process that I’ve found works best for small teams of about 5-12 people. I’ve seen major elements of it presented under a few different names: Short-Lived Feature Branch flow, GitHub flow (not to be confused with GitFlow), and Feature Branch Workflow are some. Here’s a practice I use personally and encourage within my open source projects and any small teams I run for work.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)